A survey conducted by World Bank on the post COVID-19 aftermath in Burundi has shown a rise in the quality of primary education which has been attributed to the government’s decision to invest in human capital.

The report adds that, Burundi understood that investing in human capital would be the only way the country will transform itself.

Considered as one of the nations on the continent which has not deeply been hit by the Coronavirus pandemic, schools across Burundi remained open, students in all levels completed successfully the year and have since resumed the 2020-2021 classes.

606 remain the official Covid19 cases with one death as of November 2020.

But how did Burundi succeed in uplifting its education system and subsequently emerge one of the top best performer among the French- speaking countries in Africa?

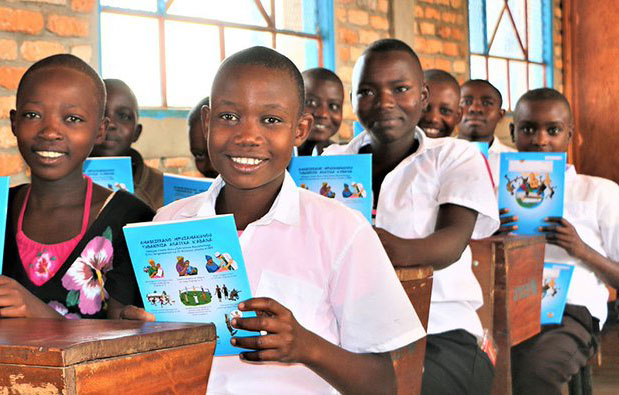

World Bank reports that by introducing free primary education in 2005, Burundi has greatly increased school enrollment and school completion, especially in the early grades. A conscious decision to ensure gender parity and push girls to attend early grades has resulted in parity in primary education since 2012.

“Quality of learning has also significantly improved. Results from “Programme d’analyse des systèmes éducatifs de la CONFEMEN” (PASEC) 2014 shows that not only are children in Burundi performing better than their peers in other Sub-Saharan African Francophone countries in reading (in grade 2) and mathematics (in grades 2 and 6), but it is the only country to have a high national score and a low level of inequality between the results of the best and weakest pupils at the end of primary,” says World Bank

“Learning assessment results are consistent with the results from the Early Grade Reading Assessments carried out in 2011 that indicated that 40% of grade two students were independent readers, 40% could read partially, and only 20% were non-readers,” adds the report.

Primary school children in Burundi are performing better than primary school children in other countries in Sub-Saharan Africa.

Burundi is the sixth top performer (out of 42 countries) according to the Harmonized Test Scores of the Human Capital Index.

Since the start of free primary education, literacy rates, especially for youth, have significantly increased, from 62% in 2008 to 88% in 2017, ranking Burundi among the top 20 countries in Africa. Such impressive results have been achieved in part due to instruction in Kirundi (local language spoken by 98% of the population) in the early grades, a cadre of qualified, dedicated and experienced teachers, and an engaged community that supports the governments’ education efforts at the local level.

The Early Grade Reading Project, supported by the World Bank, contributes to these efforts by strengthening curriculum, teaching and learning resources in the primary grades, expanding school feeding, and providing school kits.

The project, designed pre-COVID-19, was forward-looking in that it covers awareness of parental support to ensure on-time school enrollment as well as uninterrupted attendance and progression of children.

However, significant challenges still remain. While completion rates have significantly improved since the introduction of free primary education, they still remain below the average of the Sub-Saharan Africa region and other low-income countries: 4 out of 10 children do not finish primary school and 7 out of 10 do not finish secondary school.

This is partly due to demographic pressure, which leads to more and more children progressing through the education system.

The influx of children has put a strain on teaching and learning resources, particularly in critical foundational subjects such as French (along with Kirundi, French is an official language of Burundi). With an average size of 4.8 people per household and a fertility rate of nearly 5.9 children per woman, the population is expected to more than double by 2050. The ever-growing demography has been a challenge for basic services in education,

(Source: Nasikiliza).